|

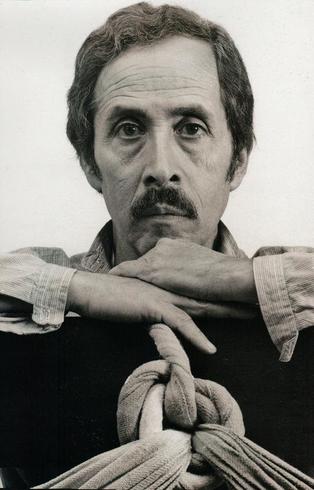

Eielson's Biography

Jorge Eduardo Eielson was born in Lima Peru in 1924. His mother was Peruvian, from the capital city, and his father was of Scandinavian origin (the grandfather had arrived in Peru at the end of the preceding century and remained there until his death). His father’s premature death, when Jorge was just seven years old, left him with a liberal upbringing. Jorge, raised by his mother, sister, and a brother, who like their father died prematurely, demonstrated even as a small child striking artistic tendencies. For the artist these tendencies were innate and manifested themselves in various ways: playing the piano (the family loved music), drawing copiously, reciting excerpts of his favorite authors, or inventing objects with anything he could find. In various interviews Eielson expressed a connection between his composite cultural origins (my four cultures-he says- Spanish, Italian, Swedish, Nazca-an ancient pre-Hispanic civilization) and his varying creative interests, as well as his scientific, philosophic, and religious curiosities. During this time, the Peruvian capital was not plagued with the oppressive living conditions that exist today (a downgrade that Eielson describes with fantastic vision in the novel Primera Muerte de Maria at the end of the 1950’s.) There is relative economic stability, cultural growths are rich and open to influences from major international centers. The young generation is nurtured, therefore and above all, by European culture. Eielson learns English and French, reads Rimbaud, Mallarme, Shelley, Eliot and other authors in original languages, as well as Spanish mystics and classics of the Golden Century, and Spanish poets of the 1900’s. He also reads the major American poets, Poe, Whitman, Dario, Vallejo, Neruda and Borges. Always a rambunctious student, Jorge changes schools numerous times until, at the end of his secondary school studies, he encounters Jose Maria Arguedas, his Spanish language professor. Arguedas, captured by Jorge’s dolescent talent, introduces the very young Jorge to the artistic and literary circles of Lima. It is Arguedas who also imparts Jorge with knowledge of ancient Peruvian culture, a cultural history unknown to the young people of the time ( a result of colonial education). In 1945, at the age of twenty one, Eielson wins a national poetry competition and one year later a national theatre competition. In these years Jorge creates his first canvases, of which the influences of two very important artists is evident: Klee and Mirò. Although Eielson did not favor academic instruction, thanks to the friendship of Ricardo Grau ( the director of the Academy of Beautiful Arts in Peru and famous Peruvian artist), he enrolls in drawing and painting classes. Shortly after, however, Grau-a cultivated and modern man, trained in Paris at the atelier of Andrè Loth- persuades Jorge to stop attending the courses, maintaining that they were inadequate for the talented artist. In 1948 Eielson exhibits for the first time in a gallery in Lima (the only existing gallery at the time) a group of works that are testimony to his natural versatility. The exhibition consists of drawing, acrylics, oils, constructions with burned and colored wood, surreal objects and metal movils or mobiles. During the same time, Jorge writes for various local publications and, in collaboration with Jean Superville, son of the great French poet, Jules Superville, curates an art review and lecture entitled: El Correo de Ultramar. Also in 1948, Jorge travels to Paris on a scholarship offered by the French government. In the great European metropolis, the young Latin American, feels at home. Right away he frequents the Latin Quarter, which, at the time, was filled with existential effervescence. In the company of international writers and artists, Jorge passes many days and nights at the caves of Saint Germain des Près, in the extraordinary hub of creativity that was post-war Paris. Also around this time, Eielson discovers the art of Piet Mondrian and a short time later, together with the Madi group ( lead by Arden Quine who, in Buenos Aries has a following that numbers the likes of Lucio Fontana, Tomas Maldonado, G. Kosice and others), is invited to the first exhibition of abstract art, il Salon des Rèalitès Nouvelles, founded by Andrè Bloc. Following participation in the Salon, Jorge exhibits at Colette Allendy, a avantgarde Parisian gallery. This is also the moment of his introduction to Raymond Hains, who which he remains connected by a long friendship. Through Hains, Eielson he meets other members of the Nouveaux Rèalistes group, with Pierre Restany as spiritual mentor and guiding theorists. Eielson, at this time, concludes his geometric, constructivists, neoplastic phases and goes to Switzerland thanks to a scholarship from Unesco (given for his journalistic achievements). There, Eielson meets Max Bill. In Ginevera, he returns to writing and in 1951 embarks on one of the most important travels of his life. Jorge arrives in Italy for a summer vacation with Javier Sologuren. As soon as he sets foot on the peninsula, Jorge understands Italy to be his elected land. Once in Rome, the artist asks a friend to send some books and personal effects, and so begins his long and intense exploration of his Latin roots. Eielson wins another contest, organized by the experimental center of Cinecittà Roma, to follow a course of cinematography. And, although cinema is one of his many passions, he does not stay long in the field. In 1953 Jorge exhibits his movils at the Galleria dell’Obelisco, at the time, the most sought after gallery space in Lima. There meets Emilio Villa, who writes a praising review for Eielson works in Arti Visive. Villa introduces Eielson to Alberto Burri and Ettore Colla. Eielson maintains a stimulating rapport with these great artists during his sacchi period, created at the atelier of Via Aurora. Capogrossi finds also interest in Eielson’s movils and introduces him to Carolo Cardazzo, who offer him an appearance in a gallery in Rome. Eielson, however, declines the invitation, thus marking the end of the movils stage. Eielson, waiting to re-begin his visual research, passes nearly all his evenings in Corrado Cagli’s studio, in via Circo Massimo. Here the artist is introduced to Afro, Mirko, Salvatore Scarpitta, Richard Serra and others, In these years, before the onset of Italian Pop Art (of which Eielson did not favor), he also meets some of the so-called Artisti di Piazza del Popolo, like Piero Dorazio, Achille Perilli, Mimmo Rotella, Antonio Sanfillippo, Carla Accardi, Cy Twombly, Matta. In this period Jorge writes one of his most important collection of poems, Habitaciòn en Roma and his two novels El Cuerpo de Giulia-no and Primiera Muerte de Maria. This is also the moment of Jorge’s discovery of Zen Buddhism and his rejection of literature, which he replaces with ironic writing, that is both visual and conceptual and which eventually brings him closer to figurative art. In 1959, intent on the exploration of his remote American roots, Eielson reexamines his visual work. He abandons the extreme avant-garde and adopts the use of various materials, like earth, sand (occasional importing sand from his native Peru), clay, animal excrement, powdered marble, iron, and cement, which he uses to sculpt the canvas surface. With these materials Eielson constructs an austere landscape, desolate, abstract, almost metaphysical, like the costal landscape of Peru. Following his landscapes, he moves gradually toward human images, realized through garments of various sorts: shirts, jackets, jeans, evening gowns, wedding dresses, stockings, shoes, ties, hats, gloves, etc. His interest was the symbolic social function of clothing, a theme present in his novel citations and in the poem Noche Oscura del Cuerpo, and later, a theme which he repeats in his performances and installations. Through the manipulations of garments, painted, burned, ripped, twisted and finally knotted, Eielson discovers his artistic sensitivity to fabric. Eielson is able to articulate the energy and beauty enclosed in knot-used also to vocalize language of his pre-Columbian ancestors- and in 1963 Eielson begins the first of the quipus series, using fabrics of various brilliant colors, knotted and tied on canvas. He arrives, in this way, at a true cultural synthesis, plastic, magical and symbolic while, at the same time, expressing the language of the ancient American ancestors. He is intent on a more visual aspect, operating in strict harmony with one of the fundamental elements of occidental art: the European canvas. The duality of cloth and canvas is recomposed by the artist and it becomes a new esthetic object that coincides with the spatial concept of Fontana. Thus, the duality of cloth-canvas is rendered as the protagonist of the work. The knot, however, matches to every type of civilization and parts from simple utilitarian function to a more sophisticated mythical conception, both magical and sacred. Eielson is conscious of this, and does not pretend to re-elaborate any language, but to highlight a plastic entity and a colorful preview of an almost unexplored archetypical subject. For Eielson the power of the knot, with its expressive codes, is securely had in the complex significances which they imply. The knot, is for him, a graphic sign, fundamentally esthetic-a nucleus of color. Moreover, the knot is the welding point between pre-Columbian culture and his present history, both personal and artistic. Other Latin American artists looked in the codes of the Maya and Aztec civilizations or in other forms of pre-Hispanic art, for a sign that could come to modify their contemporary language while also suggesting the profundity of their historical roots. But only Eielson knew how to find the artistic and anthropologic sediment in quipus and how to transform the ancient Queschua sign into the esthetic and semantic nucleus of its distant modern day language. Eielson’s knot however is also the moment of confront between his various expressive codes-from the picture to the cloth, to objects, to poetry, areas in which Eielson conducts his material and metaphysical research. They are illustrated in two paintings with emblematic titles: Knots like the Stars/ Stars like knots. The knot connects the sky with the earth, the body with the sky, the soul with the vital organs. From here, the infinite variations of the same knot exert multiple tensions. Moreover, these tensions create dynamic space-diagonal, triangular and rhombus- leading to a circular oasis where energy springs from the knots and then relaxes. In other times, in place of the knot, appear binds of twisted fabrics-flags, garments, or pure games of colored or neutral fabrics. They present themselves like sculpted objects liberated from any type of surface or canvas. Eielson exhibits his fist knots at the Venice Biennale in 1964, and gains prestigious international recognition, participating in important exhibitions in museums like MOMO or in the collection of Nelson Rockefeller, collecting numerous invitations to the Salon des Comparisons of Paris, and exhibiting in private galleries. In 1967 while in New York Eielson frequented the Hotel Chelsea scene where he is introduced to major American Pop-Artists and the precursors of conceptual art. When Eielson returns to Paris in May of 1968, his is filled with the creative energy he procured while in New York. In 1969 he is invited to the historical exhibition Plans and Projects as Art at the Kunsthalle Museum in Zurich. There he presents a work titled Sculpture Sotterranea, one of a series of five imaginary and impracticable objects. In this performance piece Eielson buries these objects in various cities in which the artist had lived (Paris, Rome, New York, Eningen and Lima). At midnight on December 16, 1969, in the Gallerie Sonnabend of Paris Scultura Sotterranea vernissages with Eielson present, while, at the same time, in other predetermined cities the burial occurs. In the same year, Eielson proposes to the American space authority (NASA) the arrangement of one of his sculptures on the moon. NASA responds to them by suggesting a future date, as for the moment the event conflicts with the ambitions of Project Apollo. Later, Eielson proposes the distribution of his ashes of the moon’s surface, maintaining that the Moon is nothing but the ideal cemetery for poets. The tenor of Eielson’s NASA inquiries is repeated in similar works: Balleto Soterraneo on a car in movement; the performance, Nage in the French countryside; il Concerto della Pace at Documenta 5 in Kassel; the performance El Cuerpo de Giulia-no, at the Venice Biennale of 1972; the performance Grande Quipus delle Nazioni at the Monaco Olympiad of Monaco, interrupted terrorists threats; the performance Paracas-Pyramid at the Kunstakademie of Düsseldorf, already directed by Joseph Beuys. In 1972 the novel, El Cuerpo de Giulia-no (already published in Mexico is 1971 for the interest of Octavio Paz, who Eielson meets during the later years of his stay in Paris) is published in French by the editor Albin Michel and gains warm critical acclaim. In the same year Eielson travels to Venezuela were he presents Paracas-Pyramid and a photo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Caracas. He continues, for Perù, where the Institute of Culture publishes a large portion of his poetry, with the title Poesia Escrita. He exhibits in private galleries as dedicates himself, with fervor to the study of pre Columbian art. He is interested, in particular, in the fabrics used by the pre-Hispanics, which he considers to be among the most extraordinary products of textile of all time. These rich textiles are characterized by timeless freshness and modernity as suggested by their importance to artists like Klee, Mirò, Picasso, Modrian, Torres Garcia, Matta, Keith Haring, and many others. In 1978 he is granted the Guggenheim Fellowship for a lecture in New York and in 1979 exhibits at the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. Eielson’s artistic activity continues with personal exhibitions at the Museo de Bellas Artes in Caracas in 1986, at the Venice Biennale in 1987, an exhibition at Centro Cultural de la Municipalidad de Miraflores in Lima (also in 1987) and at the Venice Biennale in 1988. In 1987, his novel Primera Meurte de Maria is published by Fondo de Cultura Economica in Mexico. In 1990, an anthology of his poems is published (edited by Vuelta of Mexico City, under the direction Octavio Paz). Also 1990 he is invited by Paz, to participate in the exhibition Los Privilegios de la Vista at the Centro Internacional de Arte Comtemporaneo. Again in 1990, Eielson holds a personal exhibitions at Istituto Italo Latinamericano in Rome, an event that signifies his return to artistic activity in Italy and also places him as a geographic and cultural nomad. While his nomadic identity enriched and diversified his various expressive modes, it also procured some misunderstandings , in both the literary and artistic fields. Eielson creates objects and installations inspired by writing, and also altruistic texts. On a literary level, Eielson is today considered one of the major Spanish language poets (his poetry was translated in eleven different languages). Eielson, however, does not accept this praise-worthy definition and instead he prefers to be understood simply, as a laborer of words, a laborer of images, and laborer of color, a laborer of space and so it follows. Eielson, in various occasions, looked to characterize his position, not simply as a protest against a system that asks for the same product, but, more importantly as an expression of his internal liberty-a liberty that allowed him to move, with extreme naturalness, from one field of contemporary artistic expression to another-a liberty which gave him a way to develop a global vision, both cosmopolitan and global. The immediacy of his research is granted through his continuous "travels" to create a network of interactive relationships-between rationality and magic, between the sacred and profane, between visual and verbal, the ancient and the modern. A twin universe that reveals the physical contemporary and does not admit to any hierarchy or fixed point. Remaining in the camp of the visual arts, responding to a question about which artist can be characterized as similar to Eielson, the artist responds, What a enormous question! I could distinguish between artist-mothers, artist-fathersI would like to say simply that I love very much my very large family, that understands the Cycladic Greek artists, the pre Hispanic artists, the Zen di Kioto artist, the sculptors of black Africa, the Florentine and Flemish painters of the Quattrocento. And then Leonardo, Goya, Van Gogh, Cèzanne, Picasso, Mirò, Malevich, Mondrian, Klee, Scwitters, Torres Garcia, Duchamp, Pollock, Burri, Calder, Brancusi, Rothko, Fontana, Klein, Hains, Manzoni, Beuys, some conceptual artists and those of Arte Povera. What better family could one consider? |